The Australian equity market is a small pond on a global scale, lagging behind its APAC peers when it comes to actionable liquidity. But there are big fish swimming around – and the waters are getting choppy. Global Trading dives in.

At the start of 2025, market participants drew attention to liquidity issues in the Australian equities market. According to Rob Nash, former head of relationship management at ASX

Markets, there has not been much improvement.

READ MORE: Australia’s liquidity drought

ASIC agrees. According to its September quarter 2025 reports, average trade sizes have been steadily falling. On-screen trade sizes for ASX averaged at AUD 2,229, and at AUD 1,479 for Cboe.

“That’s an incredibly small number. Five years ago it was about double that, a decade ago it was three or four times that,” Nash comments.

The small scope of the market has also acted to push even more trading to the close when compared to global peers. “We’re a lower liquidity market. There aren’t many alternatives for people to trade outside of the closing auction mechanism on the primary exchange,” one trader says.

While on-screen liquidity is declining as a result of more smart order routing and algos, and high-frequency traders are employing more AI tools to manage data, voice trading is still an active part of the market, Nash explains.

“Australia is a very unique kind of market. There’s still a lot of portfolio decision making and trading happening on a discretionary basis,” he says. “In the case of a large liquidity event or shock piece of news, a portfolio manager may decide to react quickly and buy or sell hundreds of millions of dollars of a security.”

In other regions, that decision would have to go through a team or investment committee. But in Australia, some managers are able to make those choices independently – and quickly.

“Block trading desks tend to be managed by senior staff, who typically deal with those fund managers and traders over the phone in human-to-human interactions. High-touch block trading continues to do well in Australia. Other regions, particularly in Asia, have been trying to emulate that practice,” Nash continues.

Despite it may seem like the two forms of trading, electronic and voice, are at odds with each other, “they’re not necessarily cannibalising each other,” Nash notes. “When the market is very active, there will be an active on-screen market, which will suit some traders, but there are also people who want to respond to big flows separately, and who have the ability to do so with the right block desk. It’s not an either/or, they tend to go hand in hand in Australia.”

Overall, average daily turnover in Australia reached four-year highs in September this year. According to Liquidnet, AUD 18.7 billion was executed in block trades during the month – 34.2% above the 12-month average, and close to record levels seen in August.

ASIC noted that dark liquidity represented more than a quarter of total value traded in September; just under 15% of total value traded was above block size and executed in the dark.

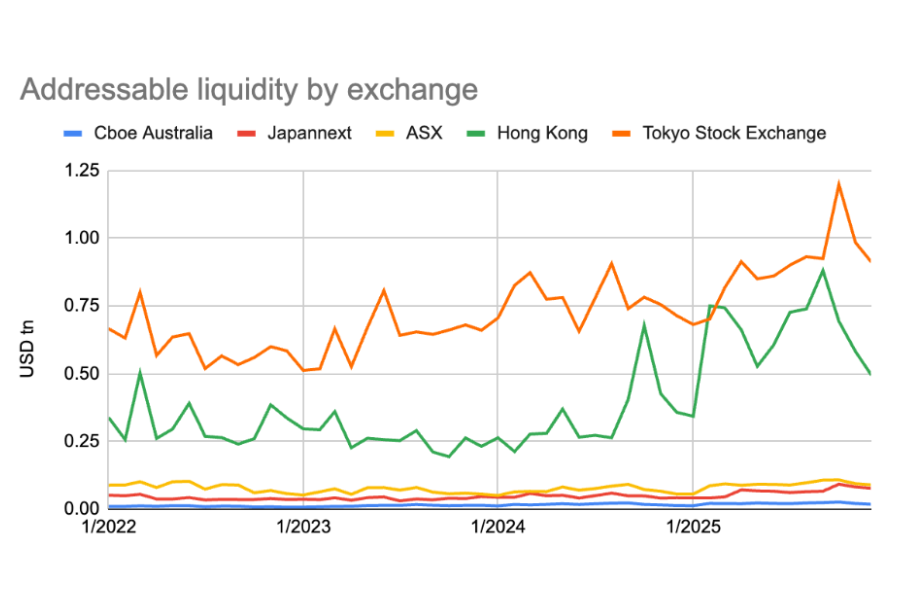

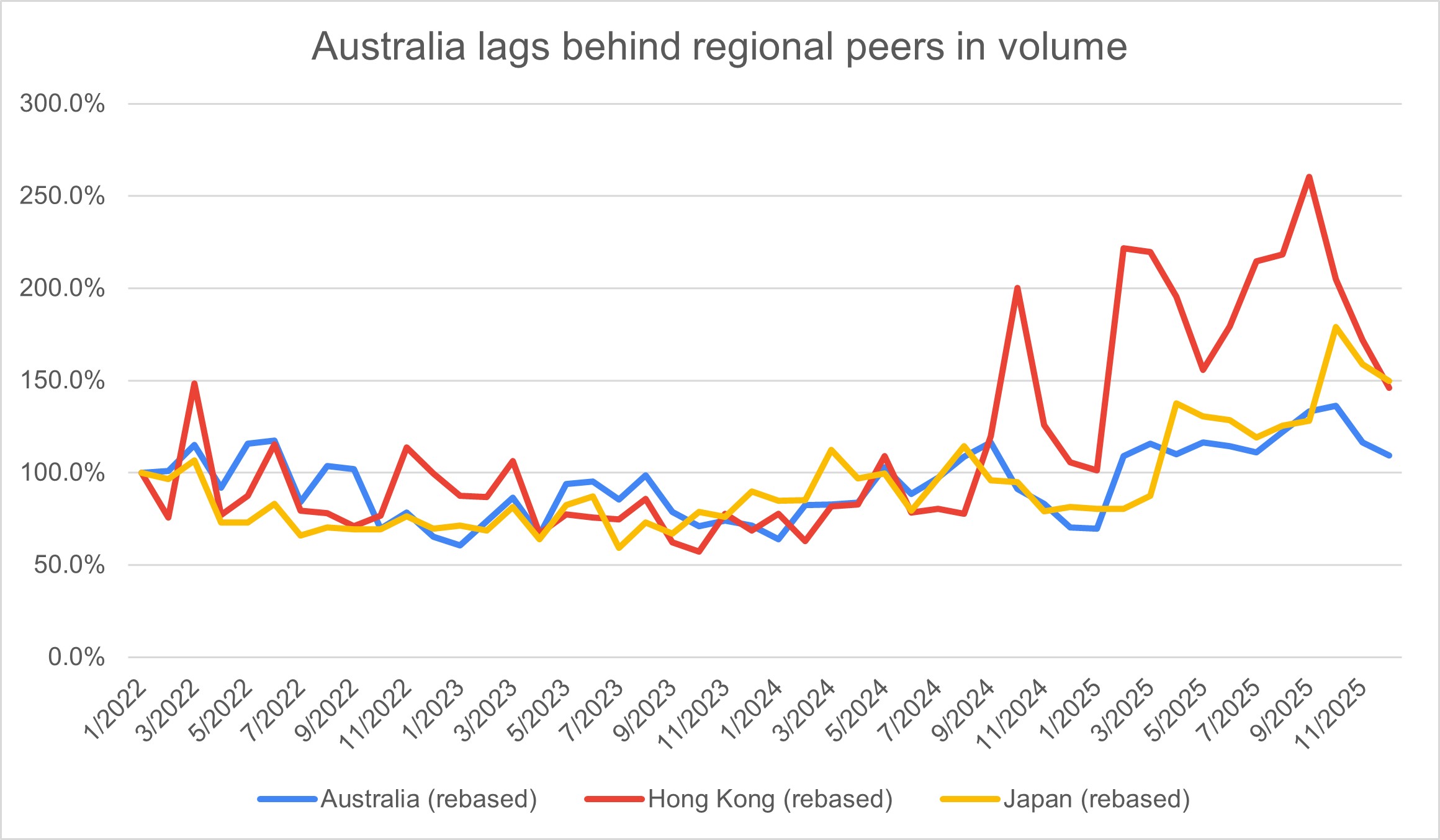

Overall, however, compared to the Japan and Hong Kong equity markets, volumes have remained fairly stagnant. In late 2025, Hong Kong’s volumes were 250% of its January 2022 levels. Japan was up more than 175%. At its peak, Australia hovered below 150%.

Going global

According to estimations in a February 2025 report produced for ASIC, ‘Evaluating the state of the Australian public equity market: Evidence from data and academic literature’, superannuation funds began favouring international listed equities over domestic listed equities in 2017.

Yet in November 2025, Brooks and Partners published an article calling Australian portfolios’ home bias a “silent killer”.

“Despite the ASX representing just 2% of global market capitalisation, the average Australian self-managed or industry super fund still holds 30-70% in domestic assets,” asserted author Luke Volker, partner and senior financial advisor the firm.

Although investing domestically can offer franking credit benefits, by which shareholders benefit from tax offsets alongside their dividends, international equities can provide better diversification – and exposure to booming sectors like technology.

“If you rely solely on Australian equities, you are effectively betting that banks, miners, and supermarkets will outperform AI, cloud computing, semiconductors, and electric vehicles for the next decade,“ Volker’s article concluded. If investors start leaning away from domestic equities, at the same time that exchanges scrap for market share and regulators try to calm the situation, Australia could see its problems worsen.

Exchanges

2025 was an eventful year for the Australian exchange landscape. ASX, the country’s largest exchange, has been embroiled in regulatory scandal, with the group under investigation following what ASIC called “serious failures” across its licensees – including the unsuccessful CHESS Settlement replacement saga.

READ MORE: ASX Group under investigation after repeated “serious failures”

In October, Cboe announced that it had received regulatory approval to operate an Australian listing market. That same month, CNSX Global Markets, which owns the Canadian Securities Exchange (CSE) acquired the National Stock Exchange of Australia (NSX) and stated its intention to build out the business and improve the competitiveness of the exchange, which currently sits in third place in the country.

READ MORE: CNSX acquisition challenges ASX’s primary listings crown

Its main competitive space will be new companies wishing to list in the country, Nash explains. “NSX lists and trades a completely different cohort of companies than those listed on Cboe and ASX.”

Then, less than a month later, Cboe announced that it was selling both its Australian and Canadian equities businesses. The news followed the closure of the company’s Japan equities business in July, and the closure of block trading platform Cboe BIDS in Australia earlier in the year. “That was a bit disappointing, and surprised a few brokers who had spent time and resources connecting to the platform,” Nash noted.

He mused, “Cboe was recently granted a license to list securities on their own exchange by the regulator, which was a key development in listings competition. That’s a very big asset that they’ve got in the back pocket which will add to the attractiveness of the business.

“I am confident they will find a new owner, most likely a foreign stock exchange, and that might happen sooner than a lot of people are expecting.”

Speculation is already brewing around who is circling Cboe Australia, which holds about a 20% share of the country’s equities market. The Singapore Exchange, SGX, denied the rumours, while the New Zealand Exchange has remained tight lipped. The CSE has expressed interest, potentially seeking to further bolster its presence down under.

Amid it all, Australian regulators are scrambling to beef up the country’s listing markets as IPOs dwindle. While results from the new “streamlined” prospectus process are not yet apparent, industry sentiment has been broadly positive.

READ MORE: Australia accelerates listing process amid record low IPOs

Technology and innovation

This surge of activity has unsettled the usually still waters of Australia’s exchange landscape. Having just four stock exchanges means that there is often little incentive to innovate in the region, market participants told Global Trading.

It is a problem that transcends the exchange space.

“Incumbents don’t see the need to change. Innovators find it hard to get people to buy in,

when those people are busy making money somewhere else. Once someone else has taken the risk and got settled in, then they might try it,” adds Greg Yanco, former executive director of markets at ASIC.

Firms are also apt to be tempted by more intriguing innovative prospects elsewhere. “A lot of companies run regional tech teams, and Australia is a smaller part of the APAC wallet,” one former equity trader notes. “If there’s something more exciting happening in China or India or Korea, then that can take away their ability to invest in Australian tech.”

After a time, not investing in technology presents more problems.

“Do you cut your losses and nurse old tech along while you do other great stuff, or try to fix everything in one go? Dealing with legacy technology is a horrible experience,” Yanco says. This is by no means a situation unique to Australia, but it’s one being felt acutely. ASX, for example, has an ongoing innovation timeline that is prioritised above opportunistic changes that may emerge.

ETFs

One area where Nash does see change occurring is exchange traded funds (ETFs).

“One of the big question marks on ETFs has been how to increase adoption from institutions, who may want to take strategic sector tilts via these instruments,” he says. “A request-for-quote (RFQ) platform would be a big step towards that goal.”

ASX has recently partnered with Japanese technology company Fujitsu, which has faced criticism in recent years over its involvement in the UK’s Post Office scandal. Fujitsu offers an ETF request-for-quote platform based on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Conneqtor RFQ platform.

“This is scheduled to be implemented sometime in 2026, and should make a significant improvement to how ETFs are priced and used by market makers, liquidity providers and issuers. It will be a big step forward in their institutionalisation,” he adds.

Also improving is how data is shared, Yanco continues. Newer ETFs offer data closer to the end of the financial year, with companies providing better data services to their customers

“I bought into some more recent ETFs earlier this year, and within the first few days of the financial year the information on them is published,” Yanco added. “Why can’t they all be like that? Often, the information you get is late, complicated and convoluted. Companies already have the data, and they wouldn’t have to do much to it. They don’t seem to realise that if they give their customers better data services, with the data they already have, their clients will be happier.”

Interest in Australia exchange-traded products has ballooned over the last four years. A September report from Betashares reported that Australian ETFs have more than AUD 300 billion in assets under management (AUM), up 36.3% year-on-year. The firm predicted that AUM will exceed $500 billion by the end of 2028.

There is a lot for market participants to keep watch over. Who will be the big exchange players in the country next year? How successful will regulatory changes turn out to be? Will the CHESS replacement saga ever come to an end? Whatever the answers to these questions will be, eyes will be on Australian equity markets in 2026 and beyond.