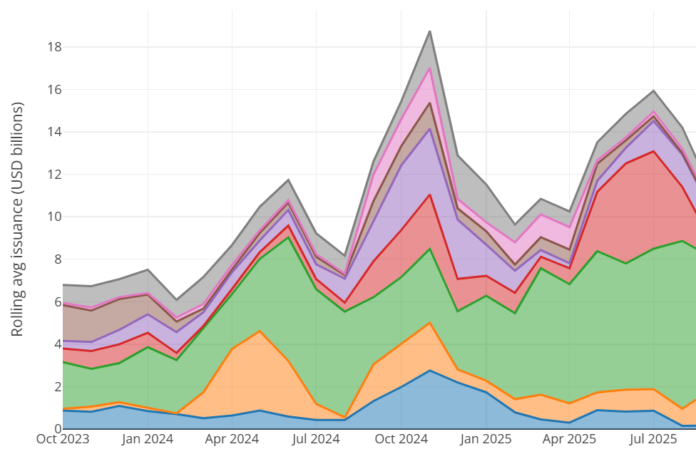

For traders, newly minted stocks are like fireworks that dazzle on their first day as volumes spike, before sputtering out into low-turnover obscurity. The summer of 2025 saw such a flurry of activity as US IPOs reached a record quarterly average volume of US$8bn.

2025 IPO activity has been strong in the US despite the April tariff shock. Priced IPO proceeds reached US$41.3bn year to date through August, up 41% on the same period of 2024, with US$19.8bn, up 61% year on year, of new equity sold to investors over the summer window, June–August.

The year’s largest US deals, according to Bloomberg, are in energy and information technology: Venture Global, the Gulf Coast LNG developer, priced lower than expected in January and raised US$1.8bn after having been scaled back; on the first day of trading, twice the 70-million-share float traded, and the stock has since been trending lower to US$14, with average daily volume (ADV) now at 8.5 million shares a day. Global Trading defines the IPO volume ratio as day-one volume/long-term ADV after day one. For VG this sits at 8.25.

In information technology, CoreWeave, the AI-infrastructure “hyperscaler”, listed in March, also after having been scaled back, and raised US$1bn, trading 41 million shares compared to the offering size of 40 million shares. The stock has traded up all year to US$130, as we write, with increasing participation. Its IPO volume ratio is now 1.3.

Figma, the design-software platform, listed at the end of July and its IPO volume ratio is now 8.05.

Klarna, the “buy now, pay later” platform, raised US$1.4bn earlier in the year, with trading activity fading fast and its IPO volume ratio now up to 16.

European activity has remained subdued despite the European Commission and the British government trying to increase appetite for European capital markets. Priced IPO proceeds totalled US$5.9bn in January to August 2025, down 52% from US$12.2bn in 2024. During the June–August window, issuance accelerated and reached US$1.6bn, 36% higher than the same months last year.

Among the largest deals in Europe, including the UK, according to Bloomberg data, Asker Healthcare priced US$1.0bn worth of stock for 126 million shares on 17 March. Its IPO volume ratio sits at 8.5. HBX Group, the travel-platform operator, sold US$776m on 7 February. Activity in the name faded fast after IPO day and its IPO volume ratio is now 55. Cirsa, the Spanish gambling conglomerate, issued US$533m on 30 June for 34.8 million shares, and trading slowed even further with its IPO volume ratio up to 80. Sectorally, issuance is strikingly different from the US, lacking the prevalence of information-technology names.

Continued steady stream of offerings in APAC, including the Middle East

Asia-Pacific, excluding India and the Middle East, has seen more robust activity all year. As of the end of August, proceeds, according to Bloomberg, were US$13.8bn, up 30% on US$10.7bn in 2024, with summer (June–August) issuance netting US$6.1bn, up 29% year on year. Larger prints covered a variety of sectors: in Japan, JX Metals, which specialises in semiconductor material, sold US$2.88bn worth of stock, selling 535 million shares and trading 176 million shares on its debut day, 10 March, with ADV now up to 28 million shares a day, having lulled after the IPO to about 5 million shares and showing renewed interest. LG CNS, the digital-transformation specialist spun off from LG, listed in Korea on 17 January and raised US$846m, with activity diving and its IPO volume ratio up to 22.

Read more: Companies race to Hong Kong for IPOs

India is the standout country of issuance so far in 2025 in terms of growth. Indian rupee-denominated IPOs raised US$9.63bn year to August, a 67% increase on US$5.77bn in 2024, with a notable summer (June to August) recrudescence of activity of US$5.95bn, up 125% year on year. The largest IPOs include HDB Financial Services, priced 1 July for US$1.49bn for 169 million shares, which traded 80 million shares on its first day; ADV has now cratered and its IPO volume ratio is now up to 80. Carlyle relisted Hexaware Technologies on 18 February, selling US$1.04bn worth of stock in the IT-services company it had taken over in 2020. ADV is now 1 million compared to 18 million on its first day.

In the Middle East—comprising the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Oman—year to the end of August, proceeds were US$4.6bn, up 80% from US$2.5bn in 2024. The summer window contributed US$1.04bn but was only 9% higher year on year, compared to more marked growth elsewhere.

All figures are in US dollars and reflect currency of issuance, according to Bloomberg. Sectors are classified using MSCI GICS methodology.